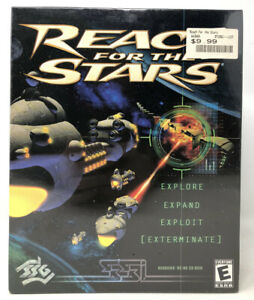

Reach For the Stars Retrospective

By Patrick S. Baker

The designation “4X” (standing for “eXplore, eXpand, eXploit and eXterminate”) originated in the Computer Gaming World 1993 preview of Master of Orion by Alan Emrich. In a play-on-words, Emrich rated the game as “XXXX”, referencing the “XXX” rating for pornography. Over time the phrase mutated into “4X” and has been adopted and adapted into a game genre description.

The designation “4X” (standing for “eXplore, eXpand, eXploit and eXterminate”) originated in the Computer Gaming World 1993 preview of Master of Orion by Alan Emrich. In a play-on-words, Emrich rated the game as “XXXX”, referencing the “XXX” rating for pornography. Over time the phrase mutated into “4X” and has been adopted and adapted into a game genre description.

A strategy game must have the following gameplay tenets to be a 4X game.

Explore: the player dispatches reconnaissance units to discover surrounding areas.

Expand: the player lays claim to newly reconnoitered areas by colonizing them, or by otherwise extending their influence into the newly discovered territory.

Exploit: the player collects and utilizes various resources in areas they control, and also upgrades the usage and collection methods of those resources.

Exterminate: the player attacks and conquers, or eliminates, their opponents.

However, Master of Orion was not the first 4X game. That honor goes to 1983’s Reach For The Stars (RFTS). The game, written by Roger Keating and Ian Trout, founders of Strategic Studies Group (SSG) of Australia, was published for the Commodore-64 (C-64).

RFTS’s design was very strongly influenced by the board game Stellar Conquest (designed by Howard M. Thompson, and published in 1974). Many of RFTS’s features have direct equivalences in Stellar Conquest. Even for 1983, RFTS’s graphics were bare-bones, but the rich management and strategic elements provided a deep and, for the time, unique video-game playing experience. In the original version of the game, the human player began with a single planet with Level 1 technology and a middle-level environment.

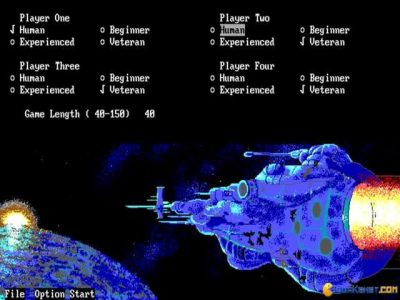

The human play could face up to three opponents, either other humans or Artificial Intelligence (AI) control. The player had limited funds and had to decide how to spend their money to best advantage on technological upgrades, building more ships (either scouts, transports, or warships), or improving their home planet’s environment.

Each turn was divided into two segments: a development phase and a movement phase. In the development phase, the player would make resource management decisions. Like how many ships to build, how much money to devote to research, etc. During the movement phase, the player would send ships to other star systems to explore, colonize, or conquer.

Each decision has mixed and uncertain outcomes. For example, improving a world’s environment means that the population grows quickly and increased industrial production, but this is, at best, a mixed blessing, because as the population grows beyond the maximum limit for that planet, the cost to support the population skyrocketed.

Each decision has mixed and uncertain outcomes. For example, improving a world’s environment means that the population grows quickly and increased industrial production, but this is, at best, a mixed blessing, because as the population grows beyond the maximum limit for that planet, the cost to support the population skyrocketed.

Concentrating on shipbuilding can stunt the player’s technological development and so on. Because the game could be played along so many different paths, it offered enormous replay value. The game’s AI offered a serious challenge in single-player games. Single-player games could go as long as twelve hours with the human player sometimes losing to the AI.

The game was well-received by the critics. Computer Gaming World’s review said the game was enjoyable and very user-friendly. The customization of each game and the AI were noted as positives. Space Gamer recommended the game highly and called RFTS “…a most addictive game” [and] “play is never the same.” The review also noted how tough an opponent the AI was.

The game sold well and in 1985 a second edition was released for the C-64 and ported to the Apple-II. This version also got some nice reviews. In 1986 Compute! termed RFTS: “a particularly fine simulation of galactic exploration,

combat, and conquest” and said it was “one of the better games on the market…” inCider gave the Apple II version three out of four stars, saying the game was “exciting…” [but] “much…of the game is a matter of juggling numbers…”

In 1987 a third edition was published, this version was strictly for the Mac-OS until it was ported to C-64, Apple II, MS-DOS, and Amiga in 1988. It was this third edition that went on to see the most widespread play and the greatest number of sales.

In 1987 a third edition was published, this version was strictly for the Mac-OS until it was ported to C-64, Apple II, MS-DOS, and Amiga in 1988. It was this third edition that went on to see the most widespread play and the greatest number of sales.

The various third editions were also well received. Science fiction legend Jerry Pournelle wrote in BYTE that the Mac version of Reach for the Stars was “certainly the best implemented” video-game version of the board game Stellar Conquest. The Space Gamer/Fantasy Gamer review said “all things considered…the game as a whole is great” despite calling the combat “illogical”.

In the early 1990s, RFTS Third Edition started to win accolades. The November 1992 issue of Computer Gaming World, in a survey of science fiction games, gave RFTS five of five stars, extolling it as: “arguably the best science fiction game ever released.” [and] “…a product still worth playing.”

A Computer Gaming World May 1994 survey of strategic space games set in the year 2000 or later gave the game four stars out of five. In 1996, Computer Gaming World pronounced RFTS the 51st-best computer game ever released.

In September 2000 a sequel for the original Reach For The Stars (confusingly also name Reach for the Stars) was released for the Windows Operating System by SSG and Strategic Simulations, Inc. In 2005 Matrix Games worked with Strategic Studies Group to update the 2000 version and released it for download from their website.

The reception to this sequel was mixed. Typically, reviewers and buyers complained about the user interface, calling it “confusing” and “bewildering” and also negatively citing the lack of detail in the tactical combat and the ship design features. Although reviewers did praise the tough AI and the much-improved graphics. This version of the game ceased being available for sale and download in 2005.

The original Reach For The Stars was an instant classic, directly inspired games such as Master of Orion, Sins of a Solar Empire, Galactic Civilizations as well as many more and can honestly be said to have started the 4X genre.

Patrick S. Baker is a former US Army Field Artillery officer and retired Department of Defense employee. He has degrees in History, Political Science and Education. He has been writing history, game reviews and science-fiction professionally since 2013. You can find some of his work at , and .