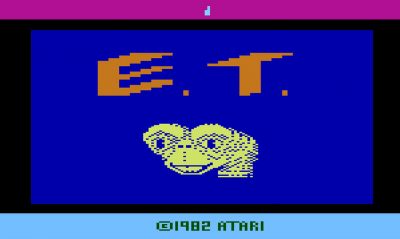

Retrospective of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial the Game

“Couldn’t you just do something like Pac-Man?” ~ Steven Spielberg

By Patrick S. Baker

By Patrick S. Baker

On the multitude of lists of worst video games of all time Superman 64 and E.T., The Extra-Terrestrial are in a constant struggle to claim the top (or is it the bottom?) spot.

In retrospect, E.T. the game looked like a sure world-class video game. The game was based on one of the most critically acclaimed and highest-grossing movies of all time. It was developed by Howard Scott Warshaw, the developer of the highly praised and best-selling Yars’ Revenge and The Raiders of the Lost Ark games. Also, it was going to be released in time for the 1982 Christmas season, when video game and video system sales generally spiked.

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial the Movie was released in June 1982 and within a month was so hugely successful that Steve Ross, CEO of Warner Communications, Atari’s parent company, started talks with Universal Studios, the film’s distributor, and Steven Spielberg, the film’s co-producer and director, to obtain the rights to create a video game based on the movie. By the end of July, the main parties had signed a deal that cost Warner Communications between $20 to $25 million dollars ($60 to $70 million adjusted for inflation). This was a ridiculously high amount for video game licensing at the time.

When Ross talked to Atari CEO, Ray Kassar, about the game, Kassar called it “…a dumb idea” but went along with developing it anyway. Spielberg, having collaborated with Warshaw on the hit Raiders of the Lost Ark game, requested that Warshaw do the E.T. game as well. Ross had promised the game would be ready for Christmas that year, leaving less than six weeks for development.

Warshaw told Kassar that he could get it done in that time “provided we reach the right arrangement”, that “arrangement” was $200,000 dollars ($600,000 in today’s dollars) and an all-inclusive holiday in Hawaii. Warshaw later admitted that committing to the short development schedule was “hubris” on his part.

Warshaw spent two days working on the basic concept of the game and then flew in a private jet to California to meet Spielberg for discussions about the game. At the meeting, Spielberg asked if Warshaw could “do something like Pac-Man?” Warshaw confessed that he was “furious” at the suggestion, but held his anger and his tongue in check, and got the filmmaker to agree to his design.

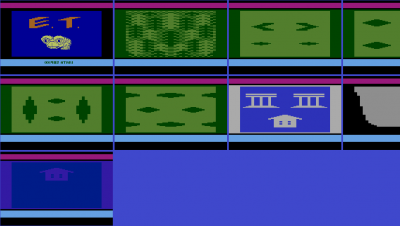

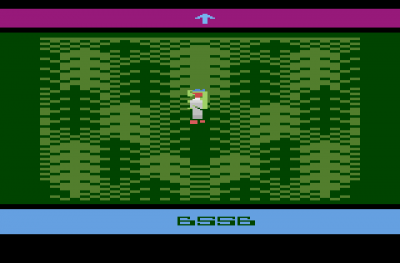

E.T. was an adventure game played from a top-down perspective. The player played as E.T. The goal was for the alien to collect three pieces of an interplanetary telephone with which to call for help. The phone parts were strewn randomly in various pits which were also scattered around the playing environment.

All actions cost E.T. energy, which was replenished through E.T. collecting Reese’s Pieces. After obtaining all three parts of the phone, E.T. must get to a place where he can “phone home”. Once the call has been made, E.T. must make it to the landing area for pick-up before a timer reaches zero.

The design and production schedule were so rushed Atari had no time for audience testing. Yet, they had such confidence in the game the company produced 5 million game cartridges.

On an aside, rumor has it that Atari regularly manufactured more game cartridges than systems existed to play them. In E.T.’s case this is not true. By 1982 some 10 million Atari 2600s had been sold in the USA, with perhaps twice that number sold worldwide.

E.T., The Extra-Terrestrial the game hit the shelves in time for the Friday after Thanksgiving, the busiest shopping day of the year. At first the game sold briskly. E.T. made Billboard magazine’s “Top 15 Video Games” sales list for both December 1982 and January 1983 with some 2.6 million cartridges sold by the end of the year. One source says that sales were largely driven by “grandmothers” buying the game for their grandchildren.

However, by the end of January, word had gotten around about how bad the game was and retailers soon found they could not sell any, even at deep discounts, and were returning unsold games to Atari. Further, regular players who were disappointed in the game also returned the game to Atari. Reportedly nearly 700,000 unsold games were returned in 1983. Then returns just poured in, ultimately one source states that some 3.5 million of the game cartridges were returned.

Some sources suggest that the game was so awful that it was a major, if not the sole cause, of the video game crash of 1983. This crash was called the Atari Shock in Japan. In 1982, the video game industry generated some $3.2 billion dollars (around $10 billion in adjusted dollars) in sales, by 1985 that number had dropped to just $100 million dollars, a decline of 97%.

No matter how desperately terrible a game was, no single game, and no single cause, triggered the collapse of the multi-billion-dollar industry. Plainly, multiple factors led to the implosion of the gaming business.

By the end of 1983, the gaming market was inundated with second-generation consoles. Besides the Atari 2600, there was the IntelliVision, the ColecoVision, the Magnavox Odyssey 2, and at least nine others.

Also, coming into this super-saturated console market were Personal Computers (PCs). PCs were coming within budgetary reach of average households. Additionally, the PCs’ ability to play games was improving as the price dropped. Add to this, games designed to play on PCs were coming to the front, games like Microsoft Flight Simulator. Lastly, PCs were capable of more than just playing games. Tasks like word processing and household budgeting gave PCs much more “bang for the buck” than a single-purpose game console.

1982 and 1983 saw a “mad rush” to release as many games as possible for the multiple consoles. Executives at Mattel, makers of Intellivision, admitted they released two years’ worth of games into the market in a one-year period. Retailers simply did not have enough shelf space for all the games for all the consoles. Lumped on top of this flood of games was the very poor quality of many of them. Not just E.T., but games like Congo Bongo, Gorf and Atari’s Pac-man, and many others were released to terrible reviews and slumping sales. These games were so bad that they caused a brutal drop in consumer confidence for all games.

Business was so bad that in 1983 Atari shipped some 700,000 game cartridges to a landfill in New Mexico and had them buried. But contrary to popular belief they were not all E.T. but also games like Pac-man, Berzerker, and even good sellers like Raiders of the Lost Ark.

All of this begs the question: how bad was E.T. as a game?

The game did get more than its share of bad reviews at, or shortly after, its release. But a 2017 meta-analysis of contemporaneous reviews gave the game a 67 out of 100, which is neutral to slightly positive score. The major negatives of the game were the poor graphics, the lack of a narrative, and the pits which were easy to fall into and difficult to escape. Players often fell repeatedly into the same pit.

Yet, E.T. wasn’t even the worst-reviewed Atari video game of the time, both Gorf and Congo Bongo (AKA Tip Top) were rated inferior to E.T.

In short, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial was far from the “worst game ever”. Likely, later public perception, particularly when the game became a subject of a website and several YouTube videos amplified the game’s poor reputation over time and developed into a reputational “a pile-on.”

Patrick S. Baker is a former US Army Field Artillery officer and retired Department of Defense employee. He has degrees in History, Political Science and Education. He has been writing history, game reviews and science-fiction professionally since 2013. Some of his other work can found at Sirius Science Fiction, Sci-Phi Journal, Armchair General and Historynet.com

Sources:

Billboard magazine, (January 8, 1983) “Billboard Top 15 Video Games“.

Bruck, Connie. Master of the Game: Steve Ross and the creation of Time-Warner (New York: Penguin Books, 1994).

Digital Press, Interview with Howard Scott Warshaw

Guinness World Records 2008: Gamer’s Edition (New York, NY: Guinness World Records, 2008)

Guinness World Records 2009: Gamer’s Edition (New York, NY: Guinness World Records, 2009)

History-Computer. (October 2022) What Was the Video Game Crash of 1983 and Why Did It Happen?

Kent, Steve L. The Ultimate History of Video Games: from Pong to Pokemon and Beyond (Roseville, CA: Prima Pub. 2001)

New York Times News Service. (January 15, 1983). “New Faces, More Profits For Video Games”.

NPR (May 31, 2017) Total Failure: The World’s Worst Video Game

ST.Game, (March-April 1984). The Best and the Rest

Video Game History Foundation. Review Roundup: Was E.T. Really the “Worst Game Ever”?

Washington Post, The, (January 14, 1986). “Many Video Games Designers Travel Rags-to-Riches-to-Rags Journey”.