Retrospective of Sid Meier’s Alpha Centauri

The Earth is the cradle of humanity, but mankind cannot stay in the cradle forever — Russian rocket scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovsky

By Patrick S. Baker

After the huge success of both Sid Meier’s Civilization I (1991) and Civilization II (1996), both released by MircoProse, another sequel was inevitable, however, it was not going to be something as prosaic as a third Civilization (although a third Civilization game was developed and released in 2001).

Instead, Sid Meier, chief developer of the first game, and Brian Reynolds, the chief developer of the second game, decided to go for something different, more of a spiritual sequel than a direct one. That something became Sid Meier’s Alpha Centuri.

The various moves and decisions of MicroProse’s and its parent company, Spectrum Holobyte’s, management, which lead to Meier, Reynolds, and Jeff Briggs breaking ties with the companies and forming Firaxis Games in 1996 have been discussed elsewhere. The Firaxis team had left the Civilization Intellectual Property and name with MicroProse, so despite wanting to do another turn-based, “explore, expand, exploit, and exterminate” (4X) strategy game they couldn’t just do another Civilization. Plus, they wanted a fresh focus other than world history.

Reynolds wrote in the Alpha Centauri Manual: “We were known for history-based games. We knew a lot about history and historical games… (but had just done Civilization II) and needed a fresh topic, so at some point, someone said ‘well, how about a future history’ – human history from the near to the distant future.”

Apparently, none of the team were science-fiction fans, so they started to read “classic works of science fiction”, such as Frank Herbert’s The Jesus Incident and Dune, A Fire Upon the Deep by Vernor Vinge, James P. Hogan’s Voyage from Yesteryear, and others. From the start the team “set out to capture the whole sweep of humanity’s future. Not just technology and futuristic warfare, but social and economic development, the future of the human condition, spirituality, and philosophy.”

The backstory of the game is a sort of continuation of a Space Race victory from Civilization II, where one nation reaches the Alpha Centauri star system with a colony mission. In the game, the United Nations sends the slower-than-light colony spaceship Unity to Alpha Centauri’s habitable planet (called with breathtaking originality, Planet).

Just before the start of the game, a reactor malfunction on Unity brings the crew and colonists out of suspended animation and irreparably cuts communication with Earth. The captain is murdered, and the rest of the ship’s leaders form factions from followers with conflicting programs for the future of the colony. As Unity breaks up in orbit around Planet, seven escape pods, each containing a faction, are scattered across the new world.

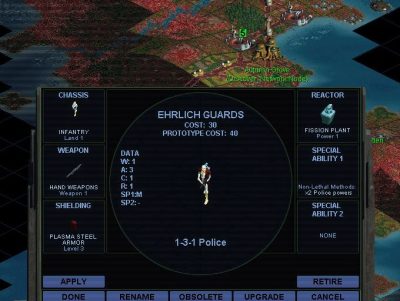

Alpha Centauri built on the base of the first two Civilization games. Therefore looks a lot like a mere “sci-fi re-skin” of those games, but it is much deeper than that. The largest differences are that the player selects, not a nation-state, but one of seven factions. Each with their own specialties, advantages, and disadvantages. The factions are:

Gaia’s Stepdaughters, pacifist-environmentalists.

Human Hive, radical communist-authoritarians.

University Of Planet, libertarian-scientists.

Morgan Industries, laissez-faire capitalists, and industrialists.

Spartan Federation, militaristic survivalists.

The Lord’s Believers, contemplative religious believers.

The Peacekeeping Forces, humanitarians, and bioengineers.

Also, instead of barbarians, the player must deal with the native lifeforms. There is the red native semi-intelligent fungus, called the xenofungus which covers large swaths of the planet. Xenofugus hinders movement and cannot be built on. It also spawns the mind worms which can conduct psionic attacks against the colonists. Other, larger, and more aggressive lifeforms also appear. Later in the game, the player learns that the native life on Planet is one giant hivemind.

Further, besides the usual military, diplomatic or economic victory the player could win an Ascent to Transcendence victory by moving humanity on to “the next step evolution…”

After some two and half years of development by Firaxis, Electronic Arts published Sid Meier’s Alpha Centauri in February 1999.

Alpha Centauri has an aggregated review score of 92% on GameRankings and 89% on Metacritic. Reviewers called it: “brilliant”, the “Holy Grail” of strategy games, and “A sublime, turn-based, empire-building, strategy game.” However, some reviewers said the game lacked “innovation” and one said he couldn’t “help but feel like I have played it before.”

Alpha Centauri has won several Game of the Year awards, including “Turn-based Strategy Game of the Year” award from GameSpot and “Computer Strategy Game of the Year” from The Academy of Interactive Arts. Further, PC Gamer US magazine named Alpha Centauri their “Best Turn-Based Strategy Game” of 1999. In 2000, Alpha Centauri won the Origins Award for Best Strategy Computer Game of 1999.

Yet, despite the great reviews and many awards, Alpha Centuri sold fewer copies than the other games in the Civilization franchise. It was just the tenth best-selling computer game of the first half of 1999 and finally sold some 225,000 copies by the end of the year in America.

There were no direct sequels in the game, but the expansion pack called Alien Crossfire was released in November 1999. The expansion pack added seven new factions, two of which were non-human, and included new technologies, new facilities, new secret projects, new alien life forms, new unit special abilities, and new victory conditions. Alien Crossfire was a runner-up for Computer Games Strategy Plus magazine’s 1999 “Best Add-on of the Year” award.

Patrick S. Baker is a former US Army Field Artillery officer and retired Department of Defense employee. He has degrees in History, Political Science and Education. He has been writing history, game reviews and science-fiction professionally since 2013. Some of his other work can found at Sirius Science Fiction, Sci-Phi Journal, Armchair General and Historynet.com

Sources:

Computer Games Strategy Plus April 2000

PC Gamer Magazine March and April 2000

“Brian Reynolds Interview” IGN.

The History of Civilization Gamasutra

Sid Meier’s Alpha Centauri Manual.

“Designer Diaries: Alpha Centauri“. GameSpot.

“Good Old Reviews: Sid Meier’s Alpha Centauri”. The Escapists

Sid Meier’s Alpha Centauri. Prima’s Official Strategy Guide.

Sid Meier’s Alpha Centuri Reviews at Metacritc

Alpha Centauri The Escapist