Napoleon’s Battles -Looking Back Thirty Years

By Jim Naughton

Introduction

The Wars of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars are sometimes regarded as the ‘Second’ World War, with the Seven Years War regarded as the ‘First.’ Battles raged on all continents save Antarctica and Australia as small forces of the primary contestants sought to seize colonies or disrupt colonial empires.

America’s War of 1812 was triggered by Britain’s high-handed naval policies – in turn a response to Napoleon’s Continental System. A Corsican general brought the war to Egypt, handily defeating the Sultan’s armies, but failing in face of unavailing British seapower. A little-known British General’s career took off in the Indian Subcontinent fight

ing native armies with some connection to French mercantile influence. That career reached its zenith when the Corsican adventurer and the British General clashed at Waterloo, bringing Europe six years of fragile peace. Clausewitz’s On War and B.H. Liddel Hart’s Strategy have their roots in the Napoleonic Wars.

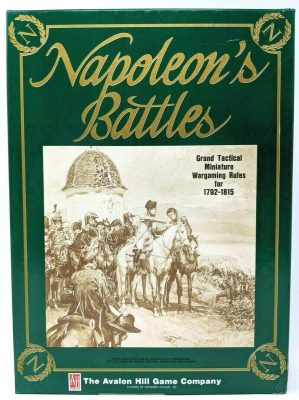

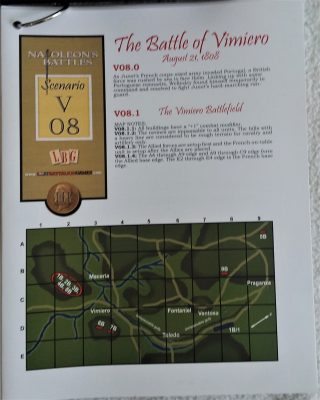

In 1989 a big game company of the day, Avalon Hill, published Craig Taylor’s and Bob Coggins’ Napoleon’s Battles. This was a departure from Avalon Hill’s normal hex-based strategy games. Instead, the game included counters designed to move freely on the tabletop and thin cardboard ‘terrain.’ No maps. The three booklets openly invited the owner step-up to miniatures. The Scenario Booklet covered six historical scenarios and two fictional ones.

Avalon Hill went on to publish two supplements. The Module of 1990 provided 8 historical scenarios, a 400-point demonstration game, and introduced new terrain plus optional rules. Module Two of 1994 introduced ‘unknown tabletop terrain’, five additional historical scenarios, more optional rules, and provided a campaign system designed to work with Empires in Arms, an Avalon Hill game on the period at the strategic level.

Then came a bump in the road – while the system enjoyed great popularity at USA Conventions, the Avalon Hill company folded its tent, selling off its intellectual property rights.

Several years later the authors unsnarled this. The Second Edition was published by Five Forks in 2004. The original three booklets were compressed into a single soft-cover volume. Four new scenarios and a revised Waterloo scenario were included. Most of the content from the RED and BLUE books was absorbed, and the errata published in the two modules were included The playing aids found in the original set were not available.

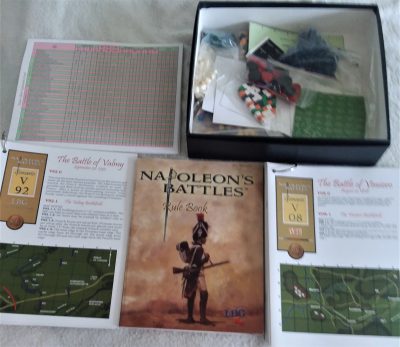

The third edition came just five years later. Lost Battalion Games produced a boxed set and a couple of supplemental scenario sets. Game aids were back.

Craig passed in 2012 and Bob went looking for a team to carry on the banner, finding it in Javier Gamez and Antonio Diaz. The Marechal (fourth edition) hit the presses in 2015. The format is similar to the second edition, but with even less of the ‘welcome to miniatures gaming’ content. Unlike the second and thirt Editions, the fourth Edition takes on issues that have bedeviled the game since publication. It is a worthy successor and well-worth acquisition.

Then Bob passed in 2016. The game’s fate is squarely in the hands of the successors.

The Core Game

Napoleon’s Battles was designed from the outset to focus the player’s attention on the grand tactical level of the black powder battlefield. To this end, it employs a move-countermove system, with limited options for the stationary player. For example, the moving player moves all his units, and the stationary player’s units may make Emergency Formation Changes in response.

Then the stationary player may ‘React’ marked units responding to his opponent’s moves. These units are usually cavalry. Then the moving player can move his units marked with ‘React’ counters into combat contact with the opponent’s reacting units. Lastly, the stationary player may voluntarily rout units to get them out of hopeless situations if not already in combat contact.

Next, the players both fire everything, with the stationary player shooting first. Then combat contacts are resolved. This may result in cavalry of either side making ‘Recall’ moves. Finally, a Pursuit Phase allows the moving player unit’s with ‘React’ to move, and the stationary player counters with any remaining relevant ‘React’ units.

Players now flip roles, and the process repeats, together constituting a 30-minute segment of time.

Command was simulated by giving each general four ratings: command span, quality, response, and combat modifier. Command span represents how far away a general can influence subordinate leaders or troops (generally speaking, not both). Quality from Poor to Excellent affects many non-combat die rolls (like rallying routed troops). The response rating gives the die roll necessary to activate the commander if he finds himself out of command. The combat rating is a direct modifier to Combat (but not Firing).

Command span is increased from a table that cross-references nationality and command level, with the nations who had organized staffs benefiting from larger boosts. Units completely out of command typically don’t move (except voluntary rout) but various poor command situations may allow half movement. A friend described it as the ‘rubber band’ theory of command control.

Troop scale is one figure represents either 120 infantry or 80 cavalry. One cannon equals a battery, but the designers only represent heavy field artillery (12-pounders and large howitzers) or horse artillery (batteries with all-mounted crews, or crews completely riding on battery equipment). Medium foot artillery is ‘factored in’ to the infantry ratings.

Unit sizes were limited. Infantry could be between 16 and 28 figures. Cavalry units, between 12 and 20 figures. All mounted on 4-man bases. Representing between 1,900 and 3,300 infantry or 900 and 1,600 cavalry. In the Napoleonic Wars, there was no agreement on a common organization – a regiment ranged between 500 men (British) and 4,000 men (French or Austrian) so the maneuver unit of Napoleon’s Battles is effectively a brigade or large regiment. At the end of a bitter campaign, a Division might be represented by a single unit. The attraction of the scale is the French Waterloo Army can be represented by 700 figures instead of 1,400 or 2,800.

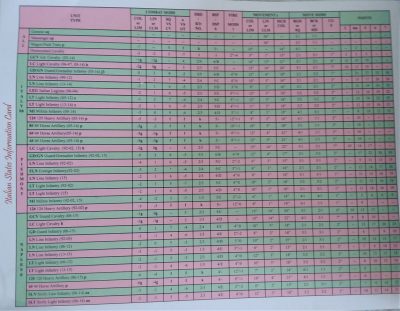

The generals’ list eventually topped 1,300 names and ratings for all the common troops of the European participants (including Turkey) rounded out the data. The troops have combat ratings for four basic formations (Column, Line, Square) and ‘vs. OTR’ with cavalry omitting the rating for Square. ‘Vs OTR’ is shorthand for several combat situations, and the OTR ratings can generally be assessed as ‘Infantry=toast’ and ‘cavalry=golden.’

Units have Disorder and Rout numbers, representing the number of hits in a single fire step or single combat that are required to cripple the unit. They have a Response number used to make emergency formation changes or similar, and a Dispersal letter that cross-indexes with unit size to tell the player when the unit is removed from play. Infantry and artillery units have a range and fire modifier. All units have movement factors for each possible formation, and modifiers for rough terrain, backing up, and changing formation. Finally, the unit rating charts give point values for building armies instead of using historical OBs.

A play sheet (front and back of a single page) gives the player the common modifiers and ancillary rules effects like weather.

Combat Mechanism

Firing represents the action of skirmishers and light artillery. Combat represents the clash of steel as well as close-range infantry firefights.

Both Firing and Combat required the players to make an opposed die roll with D10. After adjusting for troop type, formation, condition (disordered is bad, routed is worse), combat situation, and presence of generals, the highest score wins. Winning has different effects depending on the type of combat.

In Firing, there are three possible outcomes – miss, a single casualty, and two casualties. Beating the opponent’s score causes one casualty. Two casualties are the result of DOUBLING the opponent’s score. However, if the target was artillery, DOUBLING the score is required to score one hit.

Fire is done by the stationary player, then by the moving player. The shooting unit can’t hurt itself. The moving player can arrange concentrations of fire, but the stationary player can disrupt the concentration by disordering one the suspected attackers. Two Hits disorder most (not all) units. A unit can be disordered or even routed by a succession of hits – all hits in the same fire step are cumulative.

Combat only occurs between touching units. Unlike some rule sets, there is no requirement to align bases to achieve contact – only a requirement to move straight ahead the last inch before contact. When multiple units engage in overlapping contacts, the moving player ‘divides and marks combats’ so that each contacted stationary unit is fought by at least one attacker.

The opposed die roll is modified for both sides by their unit ratings, attached generals, unit status, terrain and occasionally weather (there are rules for blunder combat in limited visibility). Unlike Firing, the net dice difference affects the ‘modifying unit’ and is the casualties applied to the loser, limited only by the unit’s Rout number.

In the 1st Edition, combat continued until one side routed. But Avalon Hill liked layered rules, so an Advanced Rule provided for Withdrawal Movement – a disordered unit breaking off short of rout. Starting with second edition the Advanced Rules disappeared, and Withdrawal Movement became ‘Standard.’ The Withdrawal Move requires another opposed die roll, modified by General’s Quality (not combat rating) and the Response numbers of the involved units. Since this was defined as movement, the casualties incurred in Withdrawal were additive to the Combat losses.

Representing minor casualties and details to escort prisoners, the victorious unit who caused a Rout took a Winner Loss.

Cavalry who fail to rout an enemy bounce out of combat disordered, and attacking squares have special rules minimizing combat casualties.

Winning the Game

There are two ways of winning – breaking an enemy army or victory points. The second method is applied to battles where the game ended with both armies still fighting.

Breaking an army requires dispersing, routing or capturing units equal or greater than its ‘Army Morale,’ which is typically 60 percent of the starting total of infantry and cavalry units. Elite units (such as the Old Guard) count for more than normal units, and some units (like Cossacks) don’t count at all. In first edition, that ended the game.

In second and subsequent editions, if the number of units removed from play PLUS the value of routed units exceeds the Army Morale, the game isn’t over. Play continues until enough units leave the table to end the game, or the player rallies sufficient units to get his army out of jeopardy. During the interim, the Army is ‘fatigued’ and no units may advance unless enabled by React markers.

Victory points are scored by seizing key terrain and destroying figures/stands (the method varies with Edition).

Warts

The authors deliberately removed all the fine-level detail from the game, only presenting the players with top-level decisions and ‘factoring in’ much of the gradation of unit and artillery types. For example, Hussars, Chevauxlegers, Lancers, Dragoons, Light Dragoons, Mounted Jagers, etc. are all ‘Light Cavalry’. Much heartburn with this has been expressed over the years. After having a little heartburn myself, I discovered the variation in the opposed die rolls washed out any fine tuning I might make. Indeed, it is factored in!

Another complaint was the ability to move freely on the battlefield, with the only thing impeding your decisions being restricted rules about wheeling and friendly disordered/routed units.

Probably the biggest complaint was how the game handled built-up areas. The free-wheeling assault-counterattack described in the history books just didn’t happen. The typical response was using small arms and light artillery to disperse the garrison. Then the attacker occupied it. If the defender was lucky the built-up area caught fire, preventing the victory point loss or movement through the buildings.

Those warts being conceded, in my opinion, Napoleon’s Battles was the best operational-level Napoleonic miniature game for two decades.

The Marechal Edition brought some significant changes, and Part II of this story combs them in some detail.

do the later editions include the information from module #2 about incorporating “empires in arms” campaign

Good summary of NB! Which Napoleonic ruleset do you feel is currently the “best”?

Sam, sadly the original authors did not own the intellectual property rights for Empire in Arms, so the ‘unsnarling’ of the confusion following Avalon Hill’s demise prohibited reprinting.

Owen, I feel NB is the best for handling large battles. There are others close, so it depends on taste. Empire IV is pretty good at the intermediate level (60 men per figure, 2 guns per cannon model), but VERY complicated and so hard to learn. Also more than twice as expensive as NB for a given battle. At the battalion level my opinion is colored by being a part of a group that WROTE a pretty decent (and complicated) set of rules in the late ’70s. So I can’t offer an unprejudiced opinion. I will note that the wheel has turned back to the ’60s where people take battalions and wave their hands calling them brigades so large battles can be played…without much attention to ground scale. When we were developing rules we did exactly that, and inadvertently created a fire sac between Hugomont and La Haye Sainte where ‘a chicken couldn’t live.’ Eventually fixed, but a lesson, to be sure.