Ranging In – an artillery primer

By Robert Kelly

This article originally appeared in WWPD many years ago. I thought it would be worth dusting it off and updating it for those who missed it the first time or are new to the game.

In all you have to know about ranging in on a target is that you have to have guns available, an observer with eyes on the target and that you have to roll dice. In real life, it was a bit more complicated than that, but not much. Having served 18 years in the Royal Canadian Artillery I’ll explain how the Commonwealth artillery would have ranged in, but the same principles apply to other countries as well.

Artillery Forward Observation Officers (FOO) or Forward Observers (FOs) perform other duties besides directing fire onto targets, in fact, their sergeant or corporal (known as a bombardier in the commonwealth) assistants are probably better at it than they are. Their main duty is as an advisor and fire support coordinator to the infantry company or armoured squadron commander (supported arms commanders). This would include artillery, mortars, anti-tank guns, naval gunfire, and air defense. In the Commonwealth armies, the FOO’s are experienced captains, not second lieutenants, so their advice is well received by the company commander.

The other job is to report tactical information back to higher artillery headquarters. In fact, when not engaged in fire missions, FOO’s are constantly providing tactical information about the battle. This information goes to the battery command post (CP- or Fire Direction Center for Americans) and battery commander, which in turn passes it to the regimental (battalion) CP.

Now, if the FOO is the adviser to the company/squadron commander, then the battery commander is the adviser/coordinator for the infantry battalion or armored regiment (battalion) commander. The battery CP is at the gun position, but the battery commander is with the supported arms commander. The tactical information is then passed on to the artillery regiment CP which is located at Brigade HQ. As you can see it is a very fast and efficient method of sending tactical information up the line. In fact, many commanders at brigade HQ will listen in on the “Gunner Net” to get the most up to date information. The Battery Commander also ensures that the entire battlefield within his boundaries is covered by the eyes of his FOOs (and mortar fire controllers).

In battle, the company commanders will usually want the FOO right beside him to give advice on fire support and to point out targets that he wants to take care of. FOO’s like to be in a position to observe the entire battlefield. Now, these two locations are rarely one and the same so it is something that has to be worked out between the two of them. This is where radios come in handy and the FOO has the option of splitting his party, the FOO going with the company commander and his assistant going to a place of observation. The FOO will always ensure that the battery CP knows his location at all times, this is for tactical purposes, safety, and for the technical part of conducting a fire mission.

In the Commonwealth artillery, the FOOs always order fire, they don’t need to request. A FOO is always authorized to fire his own troop (four guns) or battery (eight guns). Should he wish to fire the regiment, he will have to be authorized. As part of an operation, the FOOs on that operation would become authorized to fire the guns of the regiment or higher for a fixed period of time during an operation. Even when not part of an operation a FOO may fire the regiment or higher based on the target and would get authorized after the mission has commenced.

Let’s get on with the nitty-gritty of engaging targets. When the FOO orders a fire mission he must provide the battery CP with some information. He must identify himself, give a warning order (including the number of guns he wants – either battery, regiment, division or higher or all available), give the target location, target altitude, his direction to the target, the type of engagement, the trajectory, ammunition, distribution of fire, whether wait for the FOOs command to fire, and whether to adjust (range in) or go into fire for effect. The warning order is merely something like “fire mission battery”, causing lots of scurrying on the gun position.

The location of the target is usually given as a grid reference from a map, but can also be referenced from a known location. The altitude of the target should be given as well so that the CP doesn’t have to look it up on their map while trying to compute everything else. The direction is the bearing from the FOO to the target. The CP needs to know this so that they plot the corrections from the FOO’s point of view, not the guns. A description of the target is very important both for tactical information and to assist in engaging the target with the right procedure and ammunition.

Type of engagement refers to the different types of technical missions such as danger close missions. There are only two types of trajectory, normal which is under 45 degrees, and high angle which is over 45 degrees. Only howitzers are capable of firing over 45 degrees and they need the warning to start digging recoil pits for the guns. The guns need to know the ammunition so that they can get it prepared.

Distribution of fire describes how we want the rounds to land. You can either give all guns the same bearing and elevation or you can give them individual data to have the rounds land in the same spot or along a line. The FOO can order “At My Command” so that he controls the moment of firing. He would then order “adjust fire” (in FOW ranging in) or order the guns to “fire for effect” if they had the data to successfully hit the target.

If the FOO has given the guns the grid reference to the target why would they have to adjust? These days the artillery uses GPS to come up with accurate grid references. In WW2 they had to rely on the map reading skills of the soldiers. Surveyors could be brought in to accurately fix the location of the guns, but it was not always practical or available.

By plotting the location of the target and the location of the guns on a map with a grease pencil, it was impossible to get closer than 100 metres accuracy at each end. Even if you had the precise locations of the target and the guns there are always other non-standard conditions that will affect the accuracy of the guns.

The firing tables for guns are based on things like a standard air temperature, altitude, air pressure, temperature of the propellant, wind, barrel wear, and standard ammunition weight amongst other things. Of course, these standard conditions will rarely if ever occur and this will affect where the round will land. The standard conditions for US guns were based on the firing of many rounds at the Aberdeen Proving Grounds.

To account for these non-standard conditions, we will fire a round downrange and adjust onto the target using the target grid procedure. You hope that the first round down range will actually be visible to you and not lost in woods or in dead ground. If the FOO is having trouble seeing the first round he has some options. He might give a bold correction to get it out in the open and then adjust from there, adjust with air-burst ammunition, use smoke, adjust with two guns or use a delay setting on the fuse which burrows into the ground for .05 seconds before exploding (sending up more dirt).

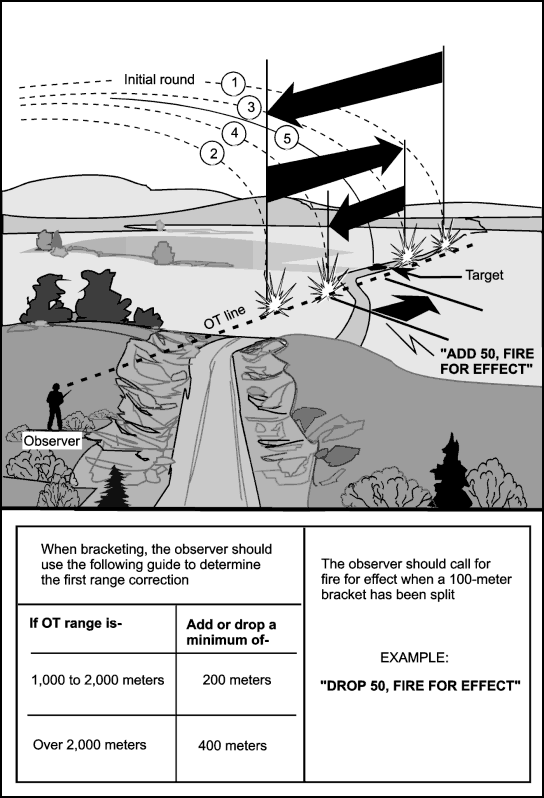

Let’s assume you can see your first round. You would then give a left or right correction to get it in line with you and the target. With experience and with a good command of the ground you might couple it with an add or drop correction, the idea being that if you have a round in front of the target, you want to get the next round behind the target. You then continue to “bracket” the target by giving corrections that are half of your previous correction.

You will continue the “bracketing” until you are on the target and you will then go into one round of fire for effect to see how the fall of shot from the entire battery looks. Determining whether you hit the target or not is not as easy as you think. The ground can play tricks on you. If you have continued to halve your corrections down to 50 metres and if you have had plus and minus rounds, you are quite confident that you will hit the target.

But let’s say after only one or two adjusting rounds you think you hit the target. Some of the signs you would look for is if the target has changed shape, if you see an orange flash on a metal object (like a tank), if dirt kicks up inside the target area or if you see smoke move through the target and the target area is obscured towards the back of the target and clear in front. Once you get a good look at the coverage from the entire battery you may want to give a small correction and go into fire for effect, which would bring a much greater fall of shot.

The diagram below is taken from “US Army Field Manual 17-19, Scout Platoon”. It illustrates the bracketing procedure. In this example, the first round landed on the Observer to Target line (OT line). This usually doesn’t happen, but a left or right correction can get into onto that line. Once it’s on that line, the bracketing procedure will commence.

There is a very quick way of adjusting rounds onto a target that works well if you are very familiar with the ground. From a point of ground that is known to the guns (either a pre-recorded target, a grid reference, or from the last round fired, you can merely give a correction using cardinal points, (north, south, east, or west) coupled with a distance and then another set of cardinal points to move it another way. For example, “North 200, West 100”. These coordinates would be in relation to how the gun sees it, so you have to be confident in your calculations and in your ability to read the ground.

There is a very quick way of adjusting rounds onto a target that works well if you are very familiar with the ground. From a point of ground that is known to the guns (either a pre-recorded target, a grid reference, or from the last round fired, you can merely give a correction using cardinal points, (north, south, east, or west) coupled with a distance and then another set of cardinal points to move it another way. For example, “North 200, West 100”. These coordinates would be in relation to how the gun sees it, so you have to be confident in your calculations and in your ability to read the ground.

When conducting a shoot, call signs are dropped after the order “fire mission” is sent to speed up the mission. All other traffic on the net is ceased, but the artillery has other nets for non-shooting traffic. All transmissions are read back to ensure that the receiver has gotten the correct data or information.

Here is a nice video on the effects of artillery fire. It’s Canadian made from the Cold War.

“G32” (pronounced Golf Three Two) a FOO party from C Battery, 1 RCHA (1st Regiment, Royal Canadian Horse Artillery) during the Cold War in West Germany, getting ready to head out to the field. Golf before a call sign indicates that they are field artillery.

Photo courtesy of the FOO, John McNair

And G32 in 1/100 scale.

At the end of the mission, target results and tactical information is sent to the battery command post, which in turn passes it up the artillery chain of command. Smart infantry and armoured officers in battalion and brigade headquarters (and higher) have been known to check the “Gunner Net” to get tactical information faster than from their own means.

Today, target grid procedure or bracketing (ranging in) is a backup way of engaging a target. Now the locations of both the guns and the observer are determined precisely by GPS. The observer fires a laser at the target and sends the direction and distance to the CP. A round is fired. If it doesn’t hit the target the round is lased by the observer and another direction and distance is sent back the CP. Another right angle triangle calculation is performed by the computer (a hardened laptop) and fire for effect is ordered and the rounds will hit the target (guaranteed).

I hope this was helpful. In my next article, I will ask the age-old question, “What are those red and white poles for”?

Here I am as a young soldier doing something technical and manning a radio on an exercise in Fort Drum New, York in 1980. Canadians are crossed trained and can multi-task.

For further reading, I would suggest George Blackburn’s trilogy.

“Where the Hell are the Guns”,

“The Guns of Normandy” and “The Guns of Victory”.

“The Gunners of Canada – The History of the Royal Regiment of Canadian Artillery, Volume II 1919-1967” by G.W.L. Nicholson. As these are Canadian books, you may not have heard of them, but they are excellent.

In fact, I took over Mr. Blackburn’s job as a FOO in the Second Ottawa Field Battery, though almost 40 years later.

Fire Plan: The Canadian Army’s Fire Support System in Normandy

by David Grebstad

Great Article!! George Blackburn’s trilogy is a must read for every WW 2 enthousiast!

Great read – I did my TQ2 mortarman with the GGFG in 82.

I was course officer for a mortar course for the GGFG and Brock around that time. I enjoyed working with the mortars. The first time I took over the parade I told the Sr NCO that the troops were standing at attention. He looked at me like I had a toaster on my head. I had only ever worked with artillery and in the artillery the troops are stood at ease when the officer takes over. Its a tradition of acknowledging the hard work done by the gunners and thus letting them stand at ease.

I also served in the Royal Australian Artillery in 103 Bty including service in Vietnam as a battery surveyor. Some years ago, I played an FoW game where my opponent had his battery of 4 guns spread out across the back edge of the table. When I pointed out that artillery doesn’t work like that, he said the rules allow it. I tried logic about setting up the guns so that the tannoy can reach each gun from the CP and that there is a central battery ammo dump that is easily accessed by each gun, but he deferred to the rules. I checked the rules and, from memory, they didn’t require guns to be together. His argument was that it avoided too much damage from counter-battery fire. For that reason and several others, I don’t game FoW anymore. Panzer Korps is my preferred ruleset.

Guns must be within six inches of the unit leader. In the past versions there was a command stand, now you just designate one of the guns. So the footprint of the battery should be about 12 inches if you are playing correctly.

I bet you have some great stories from Vietnam.