Retrospective of Vietnam ’65

“We are fighting a war with no front lines, since the enemy hides among the people, in the jungles and mountains, and uses covertly border areas of neutral countries. One cannot measure [our] progress by lines on a map.”—General William C. Westmoreland

“We are fighting a war with no front lines, since the enemy hides among the people, in the jungles and mountains, and uses covertly border areas of neutral countries. One cannot measure [our] progress by lines on a map.”—General William C. Westmoreland

By Patrick S. Baker

1965 was the year that, as one source puts it, “Vietnam Becomes an American War”. The massive bombing campaign, Operation Rolling Thunder, started. The first American ground combat units arrived “in country”. The Battle of the Ia Drang, the first major set-piece battle of the war (so well detailed in We Were Soldiers Once… and Young by Lieutenant General (Ret.) Hal Moore and Joseph L. Galloway) was fought in November that year.

It was also in 1965 that the bifurcated nature of the Vietnam War became clear. Part of the war was a conventional ground war with regular American military and Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) units fighting conventional battles against the communists’ guerrillas, called the Viet Cong, (VC or Charlie) Main Force units and the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) units.

The other part was a counter-insurgency (COIN) campaign with America and her South Vietnamese allies trying to win the “hearts and minds” of the largely rural population with generous foreign aid, civic construction projects, and Special Forces (SF) deployed to train the local defense forces to battle the VC guerrillas.

Vietnam ’65 was developed by the South African game design studio: Every*Single*Soldier. It was released by Slitherine, Ltd. and Matrix Games on 5 March 2015 for a mere $9.99.

Johan Nagel, the game’s developer, coded a prototype of the game on a Commodore 64 thirty years before it was released. Nagel said: “I coded the initial version back in 1985 for the historical society at university.” He later went on to say: “What I tried to capture. . .was the essence of the war condensed into a few hours” and to “give the player a sense of the Vietnam War…”

Johan Nagel, the game’s developer, coded a prototype of the game on a Commodore 64 thirty years before it was released. Nagel said: “I coded the initial version back in 1985 for the historical society at university.” He later went on to say: “What I tried to capture. . .was the essence of the war condensed into a few hours” and to “give the player a sense of the Vietnam War…”

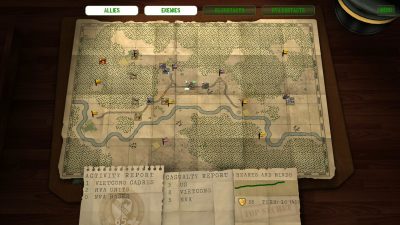

Vietnam ’65 had unique and innovative playing mechanics. In V’65 the player is a US Army lieutenant colonel assigned an Area of Responsibility (AOR) in the Ia Drang Valley of South Vietnam with orders to pacify it. However, the map was randomly generated for each game, so the Ia Drang was merely a notional setting. Each map contained 10 Vietnamese villages and varying kinds of terrain, either open, rough, rice paddy, road, village, river, and of course, jungle. At the start, the one US Army base of operations houses three infantry companies, one Green Beret A-team, three units of helicopters, one howitzer battery and one engineer company.

Vietnam ’65 had unique and innovative playing mechanics. In V’65 the player is a US Army lieutenant colonel assigned an Area of Responsibility (AOR) in the Ia Drang Valley of South Vietnam with orders to pacify it. However, the map was randomly generated for each game, so the Ia Drang was merely a notional setting. Each map contained 10 Vietnamese villages and varying kinds of terrain, either open, rough, rice paddy, road, village, river, and of course, jungle. At the start, the one US Army base of operations houses three infantry companies, one Green Beret A-team, three units of helicopters, one howitzer battery and one engineer company.

Unlike most conventional war games where victory is generally determined by occupying key positions and/or destroying enemy units, in V‘65 victory was determined by the Hearts & Minds (H&M) score. Each village started with 50 H&M points and was flying a Republic of South Vietnam flag. Anytime a campfire was shown in a village, friendly infantry units may enter the village and acquire intelligence about the enemy. ARVN units did a better job of getting information than Americans did.

Unlike most conventional war games where victory is generally determined by occupying key positions and/or destroying enemy units, in V‘65 victory was determined by the Hearts & Minds (H&M) score. Each village started with 50 H&M points and was flying a Republic of South Vietnam flag. Anytime a campfire was shown in a village, friendly infantry units may enter the village and acquire intelligence about the enemy. ARVN units did a better job of getting information than Americans did.

Entering a village might also lift that village’s H&M score. Killing Charlie and the NVA also pushed the H&M number up of the nearest village. Get the village’s score up to 60 points and it will fly an American flag and become far more likely to provide intelligence.

However, if a village’s score dropped to 40 points, it showed a communist flag and was much less likely to provide information; also, the NVA was more likely to build a base nearby. The provincial H&M score was an average of the village’s scores. A higher H&M score made enemy actions less likely. Failing to counter communist actions or losing friendly units drove the H&M score down, which made enemy actions more likely. Lose enough H&M points and the NVA built firebases and launched an invasion of the area.

The game’s currency was Political Support Points (PPs). Calling in reinforcements such as tanks, Cobra attack helicopters, heavy infantry, or Chinooks cost PPs. So does having units damaged or destroyed. Also healing, repairing and moving units, building bases and roads, and clearing jungle all cost PPs.

Having an NVA base in the AOR cost PPs. PPs were gained by destroying enemy units and bases. Run out of PPs and the player could not recruit new units, nor repair and heal damaged ones. Logistics were emphasized over combat. Units in the field could, and did, run short of supplies and the player needed to keep the choppers nearly constantly flying to deliver the beans and bullets and keep the troops moving around. Failing to keep up with logistics resulted in destroyed units and losing the war.

V’65 received favorable reviews with an aggregated score of 81 out of 100 on Metacritic.com. The reviews generally praised the innovation of the game’s mechanics. Also, actually simulating counter-insurgency within a game context was likewise lauded. One reviewer stated that before V ‘65: “Vietnam wargames…feel like just like WW2 wargames but with helicopters and more trees”.

V’65 received favorable reviews with an aggregated score of 81 out of 100 on Metacritic.com. The reviews generally praised the innovation of the game’s mechanics. Also, actually simulating counter-insurgency within a game context was likewise lauded. One reviewer stated that before V ‘65: “Vietnam wargames…feel like just like WW2 wargames but with helicopters and more trees”.

Positive reviews called the game “mesmerizing”, “fascinating” and “absorbing.” Even the mixed reviews said V’65 was “intriguing and fresh”. Complaints centered on the clumsy User Interface (UI), with one reviewer stating: “…while trying to launch a resupply mission I managed to bomb my HQ.” Others reported similar “misclicks”. Every*Single*Soldier and Nagel quickly fixed the issue and updated the UI into a much smoother and friendly form. Then, in a major update in June 2015 the developers also fixed several other fan and reviewer reported issues. The other primary complaint was that the game did not have multiple campaigns, but just the single 45-turn scenario.

To date, V’65 has sold some 50,000 copies and is still selling at a rate of just under 700 copies per month. Further, Every*Single*Soldier has, to date, produced two sequels: Afghanistan ’11 which was released in March 2017 and Angola ’86 which is in early release as of November 2023. All three games are available on Steam.com.

To date, V’65 has sold some 50,000 copies and is still selling at a rate of just under 700 copies per month. Further, Every*Single*Soldier has, to date, produced two sequels: Afghanistan ’11 which was released in March 2017 and Angola ’86 which is in early release as of November 2023. All three games are available on Steam.com.

True innovation is rare in the gaming world, but Vietnam ‘65 has innovation in spades and was one of the first, maybe the first, PC game that attempted to simulate a COIN campaign at the operational level. Further, it did so very successfully, giving gamers a real sense of the “look and feel” of the Vietnam War in a very playable format.

Patrick S. Baker is a former US Army Field Artillery officer and retired Department of Defense employee. He has degrees in History, Political Science, and Education. He has been writing history, game reviews, and science-fiction professionally since 2013. Some of his other work can be found at Sirius Science Fiction, Sci-Phi Journal, Armchair General and Historynet.com

Armchairgeneral.com (March, 2015) Vietnam ’65-PC Game Review

Encyclopedia.com Vietnam Becomes an American War (1965–67)

Metacritic.com Vietnam ’65 PC

Multiplayer.it (March, 2015) Vietnam ’65, review

Pcgamesn.com (March, 2015) Vietnam 65 PC review

Quartertothree.com (March, 2015) In the shit with Vietnam ’65

Rockspapershotgun.com (Feb. 2014) The Flare Path: On The Ho Chi Minh Trail

_____ (March, 2015) Wot I Think: Vietnam ‘65

_____ (Sept. 2016) Have You Played… Vietnam ’65?

Warfarehistorynetwork.com (March, 2015) Game Features: Vietnam 65

I’m still waiting for the definitive board/manual/analog wargame on the “Village War” part of Vietnam. I tried my hand designing two games on it: Green Beret (1996, originally but later editions and revisions, Central Highlands 1963-65) and District Commander Binh Dinh (2014, Central Coast 1969).