The Street Fighting Man in Advanced Squad Leader

By David Garvin

“Summer’s here and the time is right For fighting in the street, boy” – The Rolling Stones, Street Fighting Man. 1968.

I was reading up on some challenges of gaming recently, and the challenge the author was pondering was how to game fighting in built-up areas (FIBUA), or Military Operations in Urban Terrain (MOUT). Whichever you prefer. I cannot for the life of me find that article now but suffice it to say that the author couldn’t find a suitable game.

I cannot blame the author. Many games wish away combat in cities by simply giving the defender an advantage and maybe giving the attacker a bonus if there are engineers on the attack. But there is so much more to combat in a city. I have found that in my own gaming experiences, there is nothing that comes as close to the real thing as Advanced Squad Leader (ASL). Given the nature of combat at the squad and individual vehicle level, ASL has great utility in modeling combat with modern forces. I will explore this further in this article.

As a backgrounder, ASL is a tactical-level wargame mainly focused on the Second World War. It models combat in every theater, from the Steppe of Russia to the deepest jungles in the Pacific; from the sandy dunes of North Africa to the bocage-littered fields of Normandy. One area it does very well in modeling is that of fighting in cities. To illustrate this, one must first consider some of the “rules” of urban combat. My source is this West Point article, and some of the rules are as follows:

- The urban defender has the advantage.

- The urban terrain reduces the attacker’s advantages in intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, the utility of aerial assets, and the attacker’s ability to engage at distance.

- The defender can see and engage the attacker coming because the attacker has limited cover and concealment.

- Buildings serve as fortified bunkers that must be negotiated.

- Attackers must use explosive force to penetrate buildings.

- The underground serves as the defender’s refuge.

West Point Cadets on Parade, an institution devoted to military theory

The first two rules are related and both simply say that the defender can avoid being seen by the attacker and this gives him advantages that stem from the fact that a defender can hide within structures, using them for both hiding from the attacker and for cover from enemy fire.

Practically every structure in a built-up area offers positive terrain effects modifiers (TEM). As well, longer lines of sight (LOS) are hard to find in a city. In ASL, there is some truth to this as well. Given the dense nature of a built-up area, an enemy can maneuver out of LOS of an attacking force, even if the attacker has substantial air assets. Maintaining concealment in ASL is a force multiplier and reduces the effectiveness of enemy fire; fire is halved as area fire against a concealed unit.

The next rule, that a defender can see the enemy coming, is true if the attack is coming from outside the city or built-up area. Once inside the city, however, both sides suffer from being able to engage at a distance. If defending a village in ASL, for example, there are typically surrounding open areas that an attacker must use to approach it. A skillful enemy could use hidden initial placement for his ordnance weapons, and often a defender will have a special scenario rule that will allow for a certain amount of the defending force to be hidden in this way.

That said, most scenarios in ASL are combat within a city, as opposed to a force engaging from outside of it. There are exceptions and no other scenario depicts this as well as ASL D, The Hedgehog of Piepsk. In this scenario, a large attacking force must seize a village from defending Germans. The defenders are all hidden and the attackers must get in the village before they suffer grievous losses. In short, firing from within buildings at long ranges against an advancing enemy takes it toll. It’s true in real life, it’s true in ASL.

In real-world combat, the use of explosives to gain entry into buildings is a must, hence the next rule from real-world urban combat. This is also true in most cases in ASL. When fighting against a defender in a fortified location, entry into that location is forbidden unless the defender is pinned or is reduced to less than full squad strength.

The exception to this is if the attacker can breach the fortification. This is done using demolition charges, typically used by engineers or other such specialist troops. In ASL terms, any elite unit can use these without penalty; the scenario designer typically will use any elite force to represent engineers. That said, using any direct-fire high-explosive attack can also possibly provide an entry for attacking forces. One must also remember that flamethrowers are not affected by a defending unit’s TEM, so keep that in mind.

The last rule I’ll consider before moving on to some other facets of urban combat is that of the use of the underground. While that’s true, this is amplified by urban terrain being very much three-dimensional in nature. Out on the Steppe, it may be sufficient to consider left, center, and right as three options to attack; in a city, one must also consider up and down as well. Of all the games I’ve played, ASL is the best at demonstrating this messy way to fight.

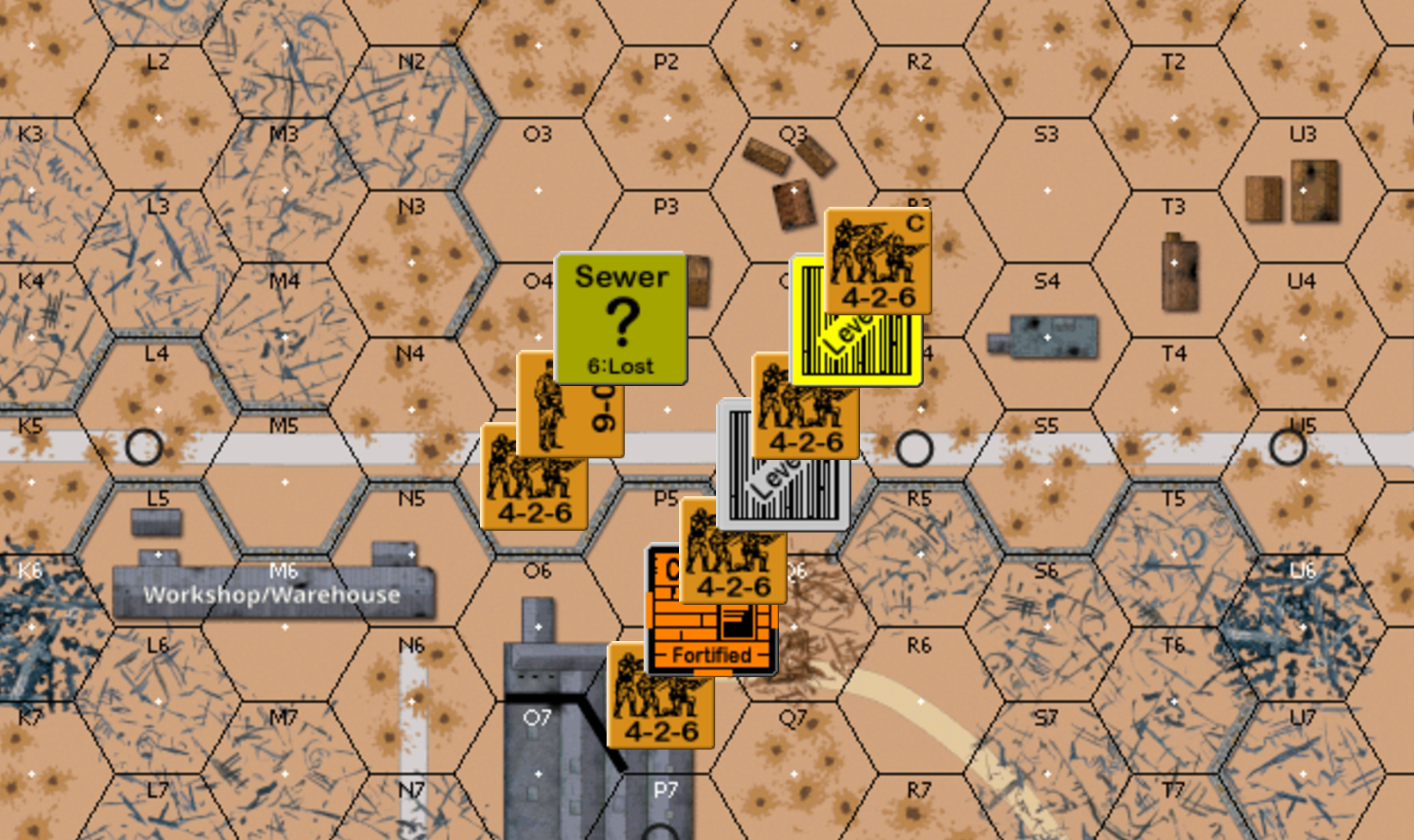

The use of level counters serves to show what level a unit is on. Then there are the sewers and tunnels! In gameplay, this will often lead to unwieldy stacks, but then again, such is the nature of urban combat. But the main thing is this: if you fight into a building, you will have to make sure you go left, right, up, and down! That’s true in real life; that’s true in ASL.

There are some criticisms of ASL when it comes to representing urban terrain. First of all is the scale; the hexes represent forty yards from dot to dot. And even the most amateur historian will know that roads are just not that wide in Europe, especially in the older city centers! The rules deal with this, allowing forces to dash from one side of a street to the other, reducing fire to them as area fire.

Another aspect of urban combat not listed is the use of Armored Fighting Vehicles within a built-up area. Even against infantry without light anti-tank weapons (LATW), even the heaviest of tanks are very vulnerable on city streets, thanks to the street fighting modifier possible for a defending infantry unit.

As a last point, the one lesson one can get out of ASL when it comes to urban combat is that the close ranges of city fighting render an attacker’s advantage of range to null. Even before I joined the army, I realized this in some of my first fights in Stalingrad. Take as an example the first-line German squad in ASL. With a firepower of 4 and a range of 6, it has triple the range of a Soviet conscript. But once within a city, where ranges are often reduced to two-hexes or less, that advantage is gone. This is true in ASL, and any historian will tell you that it was true in the fighting for Stalingrad.

In conclusion, alluding to a few rules of Urban Combat, I have shown how these rules can operate in ASL. The game is especially good at modeling the three-dimensional aspect of urban combat, as well as illustrating the vulnerability of unescorted tanks in cities. Defending infantry can be difficult to dig out of a city and to do so, will take much more time, effort, and infantry than even an attacker can sometimes afford.

This is a lesson that ASL can teach, even to the modern soldier. The weapons may change, but within the limits of any modern city, the long-range, wire-guided anti-tank missile is of limited use. City fighting is a close-in fight, and by using ASL as a tool, one can learn the awful lessons of such fighting using cardboard soldiers. That’s my experience, anyway!

David Garvin is an Infantry Officer in the Canadian Army and has instructed hundreds of military candidates, including at The Royal Canadian Regiment Battle School, The Infantry School, the Tactics School, and the Royal Canadian Armoured Corps School. Much of this instruction has been focused on Fighting in Built-up Areas (FIBUA).

Great read sir!!