Master of Orion Series Retrospective (Part One)

By Patrick S. Baker

By Patrick S. Baker

The early 1990s saw the release of many of the seminal games of what would soon be called the 4X (for eXplore, eXpand, eXploit, and eXterminate) PC game genre. Games like Armada 2525, Civilization, and the subject of this article, Master of Orion (MoO) were published some 30 years ago and still influence the genre today.

In fact, reviewer Alan Emrich named the game type “XXXX” in a 1993 preview of Master of Orion for Computer Gaming World (CGW). A year later Martin E. Cirulis in the same magazine shortened the term to “the four Xs” this later became “4X”. While MoO was not the first 4X game, that honor goes to Reach of the Stars released in 1983.

Still, it was Master of Orion that “would define 4X gaming for years.”

In 1988, Steve Barcia, an electrical engineer from Austin, Texas along with his wife Marcia and their pal, Ken Burd, founded Simtex (a portmanteau of SIMulation and TEXas) Studios. For some five years, the three worked together on a 4X game called Star Lords. In Early 1993, Simtex Studios submitted the game unsolicited to MicroProse Software in 1993. The executives at MicroProse shared the submission with gaming journalists Alan Emrich and Tom Hughes. At first blush the game was, says Emrich, “not that great”, but there was something about it and as he played the game, he liked it more and more.

Meanwhile, MicroProse had just released the mega-hit, Sid Meier’s Civilization, and thought, maybe, they had another winner on their hands with Star Lords, so the company obtained the rights to produce and publish the game. Jeff Johannigman was assigned as a producer at MicroProse. MicroProse, close to bankruptcy at the time, budgeted a mere $50,000 dollars for the project and gave the design team just four months to essential redo the whole game. Johannigman, working with the Simtex crew and a MicroProse team, took things in hand. It was also at this point the name of the project was officially changed to Master of Orion.

Johannigman, who had previously worked at Electronic Arts (EA), kept the focus of his team on the three principles of great games he learned while working at EA, saying they “…need to be simple, hot, and deep.”

Simple was easy to get into and start having fun immediately. Hot was dramatic, thrilling, and somewhat unpredictable. Deep was a mix of challenging for players and having enough depth and complexity to make the game playable multiple times. But they had to avoid making the game overly complex and forcing the player to micromanage.

Emrich and Hughes were soon offering suggestions about how to make the game better to the development team. The recommendations made by Hughes and Emrich were so beneficial that the pair would get a special credit in the game manual, and would later write the official strategy guide as well.

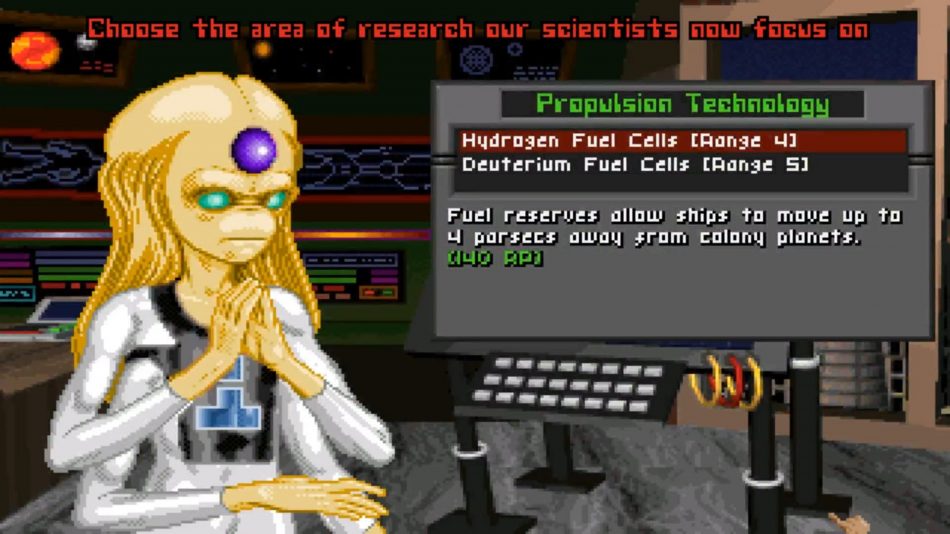

Master of Orion was a turn-based game, the single human player started with a single world, one colony ship, and two scout ships. The rest of the races were controlled by the game AI. The player could elect to play as any one of 10 playable races; each race had its own strengths and weaknesses, each racing requiring different strategies to win the game. There were different kinds of planets to be discovered and colonized, if possible, ranging from near-paradise “Gaia” planets to the deadly “Toxic” planets. The planets could have various important resources on them to be exploited.

The game program created a random map at the start of each game, based on player choices, such as the size of the galaxy and the number and strength of their opponents. The players explored the galaxy, founded and managed colonies, terraformed planets, researched technologies, build spaceships, conducted diplomacy, and waged war (on both the strategic and tactical level). Orion, the “throne-world of the Ancients” was the most valuable planet in the galaxy and protected by a powerful warship, the Guardian. Seizing Orion would almost guarantee a victory. Winning the game was accomplished by eradicating all opponents, or by winning a 2/3 majority vote in the council of races.

MoO was released for MS-DOS on 6 September 1993 and later ported to the Macintosh system. Most of the reviews were glowing. Computer Gaming World’s full review from December 1993 said: “Master of Orion is one of those games where one must actually put effort into finding something inadequate about …” and that was “…the highest praise this reviewer can give a product”. Further, the reviewer declared it “a definite Game of the Year candidate as well as Exhibit A in many divorce cases.” The CGW 1994 survey of strategic space games set in the year 2000 and later, awarded the game 4-plus out of 5 stars, stating it was “richly-textured…with high play yield.”.

Computer Games Strategy Plus named MoO the Best Strategy Game of 1993. In June 1994, CGW awarded it Strategy Game of the Year with the editors calling it “Civilization in Space.” The most noted shortfall was the lack of a multi-player option.

However, the reviews were not universally glowing. The July 1995 edition of Next Generation reviewed the game’s Macintosh port version and gave it 2 stars out of 5, calling the game a “stodgy mess.”

Even after the initial blush, MoO continued to receive honors and awards. In 1996, CGW ranked it the 33rd best game of all time. In 1998 MoO made GameSpot‘s list of the greatest games of all time and PC Gamer Magazine pronounced it the 45th best computer game ever, calling it “…great…”. In 2001, it entered GameSpy’s game Hall of Fame and in 2003, IGN put it 98th on it list of 100 top games.

Sales were brisk and by 1995 the MS-DOS version had sold over 125,000 copies. This sort of reception ensured that a sequel was soon in the works.

Patrick S. Baker is a former US Army Field Artillery officer and retired Department of Defense employee. He has degrees in History, Political Science and Education. He has been writing history, game reviews, and science-fiction professionally since 2013. Some of his other works can be found at Sirius Science Fiction, the Sci-Phi Journal, Armchair General, and Historynet.

Sources:

- Computer Games Plus: November, 2000 at http://www.cdmag.com/articles/

- Computer Gaming World Magazine Issues: September 1993, December, 1993, February 1994, June 1994 and November 1996 at Computer Gaming World Museum

- Gamesspy

- “History of Master of Orion, The” at Making Games

- IGN

- “Master of Orion” at The Digital Antiquarian

- “Master of Orion” at History of PC Gaming

- Master of Orion: The Official Strategy Guide by Alan Emrich and Tom E. Hughes, Jr. (Rocklin, CA: Prima Publishing, 1994) at the Internet Archive

- Next Generation Magazine July, 1995 at the Internet Archive

- PC Gamer US, October 1998 issue