Retrospective of Kingmaker, the Games

By Patrick S. Baker

“Peace, impudent and shameless Warwick, peace, Proud setter up and puller down of kings!” – William Shakespeare – Henry VI, Part III, Act III, Scene 3.

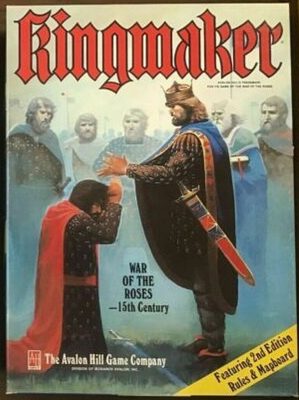

Besides being a great background for some of Shakespeare’s best plays, the Wars of the Roses make a fantastic setting for a great game: Kingmaker. Developed by Andrew McNeil and released in the United Kingdom in the fall of 1974 by Ariel Productions Ltd, a division of Philmar, Ltd. The front page of the rule book read in part: “

…. The game takes as its basis the concept that the dynastic struggle between the royal houses of Lancaster and York (called the Wars of the Roses) was, in reality, a series of brutal and bloody power struggles between factions of self-interested noble families, with the Yorkist and Lancastrian princes the pawns in a greater game of gaining control of the country in the name of one or the other monarch. Players control pieces representing the noble families as they seek power by a combination of military, political and diplomatic skills.”

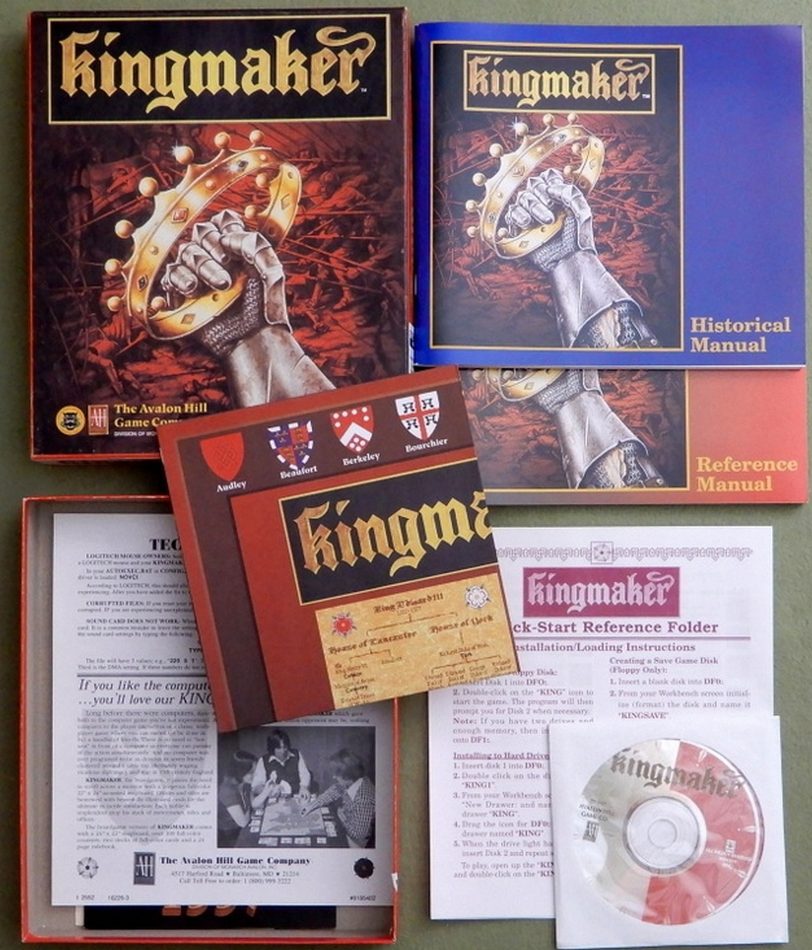

The first edition of the game was packaged in a large Monopoly-styled box and came with the game board, 38 game counter which included 23 nobles, 72 crown cards (called resource cards in the 2nd edition), and 80 event cards along with the rule book. Later editions came in a “bookcase style” box and had more and slightly different pieces.

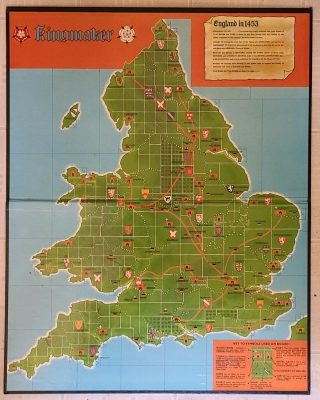

The board was a map of 15th century England (1453 in the first edition) with walled cities, towns, castles, and roads. In later editions of the game, the map also had Ireland and Calais. The map was divided into irregularly shaped areas that controlled the movement of the counters. Roads allowed for rapid movement if they were not blocked by the other factions.

Round cardboard counters with heraldic badges represented the nobles on the map. Members of the royal families were represented by square or octagon counters with their names and either a Lancastrian red rose or Yorkist white rose. There was also a set of counters with various colors and symbols which signified control of castles and towns. The ships were represented by square pieces with a ship symbol and the name of the vessel.

Round cardboard counters with heraldic badges represented the nobles on the map. Members of the royal families were represented by square or octagon counters with their names and either a Lancastrian red rose or Yorkist white rose. There was also a set of counters with various colors and symbols which signified control of castles and towns. The ships were represented by square pieces with a ship symbol and the name of the vessel.

Resource cards represented nobles, some already titled, like Neville, Earl of Warwick, and others, like Clifford, which are untitled at the start. Title cards could be bestowed on an untitled noble, such as making Clifford, Earl of Essex. Many titles also provided troops and control of towns and castles. Office cards allowed a titled noble, to receive an office like the Marshal of England, or Archbishop of York. Offices also had troops, castles, and towns attached. Other cards were mercenary units like Burgundian crossbowmen. Others were major, walled cities such as Coventry. Finally, there were the ships that allowed for quick movement by sea, into and out of ports, and to and from overseas destinations like Ireland.

The 80 events cards represented various random events in the game such as plagues or peasant revolts or invasions which could affect any of the nobles in the game, usually by making them immediately move to the location of the event. Sometimes events killed royalty and nobles.

There was no player limit in the first edition of Kingmaker, but the later ones limited the play to between two and seven players. Each player controlled a faction of nobles of the Wars and was dealt resource cards based on the number of players. Up to a total of 36 cards between all the factions were dealt. The goal of the game was to gain sufficient resources for your faction so you controlled the sole crowned monarch of England. Generally, the game cannot be won solely through military strength, but by a combination of military prowess, diplomacy, and sheer luck.

Copies of Kingmaker started to reach America by the end of 1974 where it got a bad review in Games & Puzzles magazine. Still, it collected a “cult” following. The game then appeared at America’s leading war game convention, Origins 1, which generated enough buzz to motivate Simulations Publications, Inc. (SPI), America’s top war game publisher, to import the game. Kingmaker was the 1975 Charles S. Roberts Best Professional Game Winner.

At this point, Avalon Hill (AH) sent a letter to Philmar seeking to license the game for manufacture in America. This licensing agreement required some revisions to the game for distribution in the United States. Most of these changes were minor, such as adding grid coordinates to the cards for town and castles. Other changes were larger, including things like “Mercenary Go Home” event cards, and expanding the map to include Ireland and Calais.

At this point, Avalon Hill (AH) sent a letter to Philmar seeking to license the game for manufacture in America. This licensing agreement required some revisions to the game for distribution in the United States. Most of these changes were minor, such as adding grid coordinates to the cards for town and castles. Other changes were larger, including things like “Mercenary Go Home” event cards, and expanding the map to include Ireland and Calais.

Readers of SPI’s Strategy and Tactics and Moves magazines gave the game-high ratings and readers of AH’s magazine, The General, placed it in the top third of the “Reader Buyer’s Guide”.

Kingmaker Goes Digital

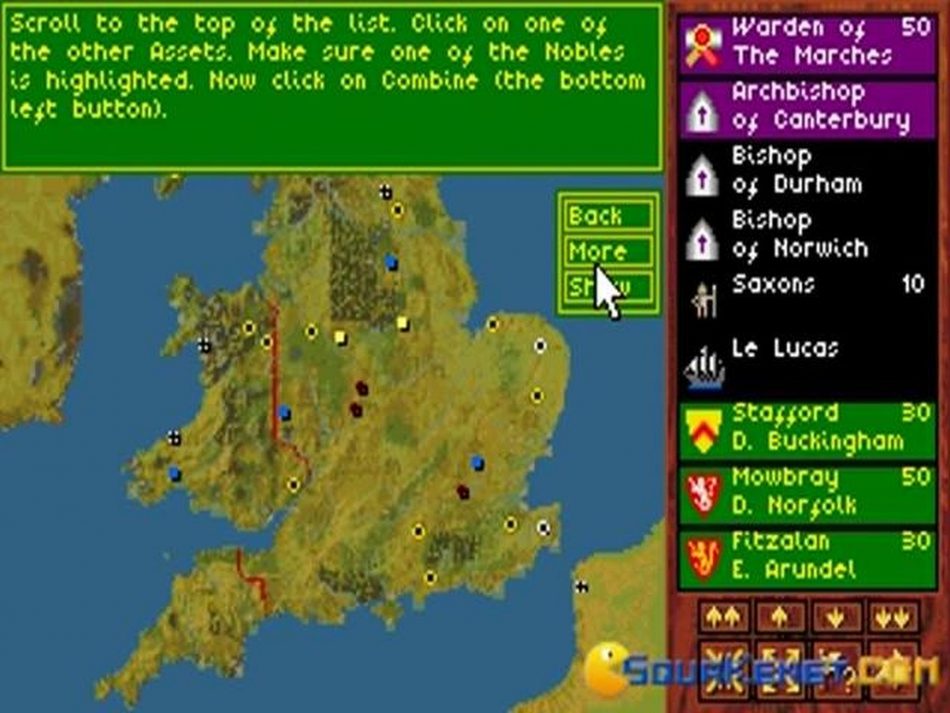

In 1993 AH release a personal computer version of Kingmaker, called Kingmaker: The Quest for the Crown in Europe, for the Amiga and Atari. In 1994 the game was ported to MS-DOS. The PC version replicated the look and feel of the board game nearly exactly and let the player compete against as many as five AI-controlled factions. The biggest change from board game to PC was a tactical mode which let the player command their army in combat, but still with the opportunity to resolve battles abstractly if they chose.

Computer Gaming World’s reviewer gave the game 3.5 out of 5 stars. He decried the lack of multiplayer, but said the game was “addictive, and a class act” and the AI was “clever and varied.” The editors of PC Gamer US nominated Kingmaker for their 1994 “Best Historical Simulation” award. By summer of 1996, Kingmaker had sold over 40,000 copies, which was considered “decent for a computer wargame” and it outsold every subsequent AH computer game.

Computer Gaming World’s reviewer gave the game 3.5 out of 5 stars. He decried the lack of multiplayer, but said the game was “addictive, and a class act” and the AI was “clever and varied.” The editors of PC Gamer US nominated Kingmaker for their 1994 “Best Historical Simulation” award. By summer of 1996, Kingmaker had sold over 40,000 copies, which was considered “decent for a computer wargame” and it outsold every subsequent AH computer game.

The game was a sales success as both board and PC games and is considered a true classic. In early 2020 a revision of the board game was announced as being in development in the UK, currently, I could find no word as to when this 21st Century version will be released.

Patrick S. Baker is a former US Army Field Artillery officer and retired Department of Defense employee. He has degrees in History, Political Science and Education. He has been writing history, game reviews, and science-fiction professionally since 2013. Some of his other works can found at Sirius Science Fiction, Sci-Phi Journal, Armchair General, and Historynet.com.

Sources:

Computer Gaming World: July 1994 and August 1996 at archive

Kingmaker at Boardseyeview

Making of Avalon Hill’s Kingmaker, the by Andrew McNeil at Diplomacy-archive.net.

PC Gamer, March 1995

Retrospective: Kingmaker at Grognardia

A great game that I miss. Would buy it again if it was to be punished one more.

Thanks for the flashback down memory lane. We played and played and played it a lot in our group. We also used it for several miniatures campaigns.

Played KM since the original came out in the 70’s. Still have both versions. Our group expanded the game board to have the entire Scottish and Ireland zones, with their actual noble families, castles, cities, and separate zonal card decks. Then went the next step and played a 47 player by mail campaign game with painted 25mm miniatures. Three referees or “COATs” (Creator of All Things) oversaw the internal movements and battles. I was COAT#2, in charge of the economics, and assistant for greater England, and COAT of Irish zone. Had it all…. the wool trade, research in the families so the players had the historical lineage, overseas travel to 1493 Constantinople (Jasper Tudor), Full parliament afternoons live in person, the king wore a burger king crown. the miniature battlefield treachery was real…. along with the black death miniature, and lots…lots more. All done before the computer age……

Awesome game. Stafford to Leeds!